A friendly, non-technical introduction to differential privacy#

A blog post series about differential privacy. Provides simple explanations and assumes no prior knowledge. The blog branches out into several articles.

1. Intro.#

Starting chapters.

1.1. Why differential privacy is awesome#

Differential privacy was introduced in 2006, after many failed attempts at methods to publish people’s data while protecting their privacy.

The core idea behind differential privacy#

As a premise, consider any data manipulation procedure (ML, stats, obfuscation, etc.). Differential privacy requires that the outcome of a process be basically the same when executed on incomplete data.

In this context, basically the same means that and outcome is equally likely from a complete dataset and an incomplete dataset. For this to be true, the process must introduce noise into the data before executing.

Briefly mentioned in the blog, a dataset is said to be \(k\)-anonymous if every combination of identifying fields appears in at least \(k\) records.

Differential privacy is a property of the process, not the data (unlike \(k\)-anonymity).

What makes differential privacy special#

Why all the hype aruound differential privacy? Three reasons, mostly:

No more attack modeling:

Most previous definitions of privacy require assumptions about the attacker. What tools, auxiliary data, goals do they have? Assumptions can be wrong, and one can’t be sure to have covered all assumptions.

Differential privacy guarantees:

Any and all data about an individual is not represented in the outcome. An attacker can’t even know certainly if any particular register was present in the dataset.

Even if the attacker knows the data partially, all other registers are protected.

Quantify privacy loss:

Previous privacy models had improper metrics to measure the degree of privacy. \(k\)-anonymity, for example, tells as that any record in a dataset looks like \(k-1\) other records. Not really a robust privacy metric…

Differential privacy can quantify the greatest possible information gain (\(\varepsilon\)). Given \(\varepsilon=1.1\) and probability that a register is in the dataset of \(0.5\), one could at most be \(75\%\) certain that the register is in the dataset (the article does not provide a formula for this).

Mechanism composition:

Given two or more different private versions of a dataset (under the same privacy model), their union will not necessarily hold those same properties. Two \(k\)-anonymous versions of the same data, together, are not \(k\)-anonymous.

Two differentially private datasets (read as “the outcome of a differentially private process”), each with the same parameter \(\varepsilon\), together are still differentially private. Less so, but quantifiably so. The new metric is now \(2\varepsilon\).

Conclusion#

Uncertainty in the process means uncertainty for the attacker, which means better privacy.

1.2. Differential privacy in (a bit) more detail#

A process \(A\) is \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private if, for all datasets \(D_1\) and \(D_2\) which differ in only one individual:

for every possible output of \(A\), \(O\). Remember, \(A\) is non-deterministic.

This is what it means for the outcome of two datasets to be basically the same. If the ratio of their respective probability is less than \(e^\varepsilon\). \(\varepsilon > 0\), when \(\varepsilon\) is close to \(0\), the probabilities are very close to one another:

Because there’s only two possibilities in this scenario, \(P[A(D_2)=O] = 1 - P[A(D_1) = O]\), and so the ratio of these probabilities is the odds.

A simple example: randomized response#

To incentivize honest answers to a survey, one may introduce plausible deniability. In a survey of illegal drug users, we devise the following experiment.

A participant flips a coin, and answers honestly on tails.

If heads, the participant flips another coin and answers

Yeson tails,Noon heads.

This means that if a participant answers Yes to being an illegal drug user, they are not necessarily admitting anything. This process is \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private for \(\varepsilon = 1.1\).

The math:

This is because a drug user will answer Yes 50% of the time, plus another 25% from flipping two coins. The remaining 25%, the drug user answers No.

This is because a non-user will answer No 50% of the time, plus another 25% from flipping two coins. The remaining 25%, the non-user answers Yes.

Introducing noise into a process will matter little for plentiful data, as the noise cancels itself out. To reduce or increase the noise, increase or reduce the probability of truth respectively.

Exercise to the reader#

With what probability \(p\) should the coin land on tails to achieve a given \(\varepsilon\)?

For example, if \(\varepsilon = 1.1\), \(p = \frac{3-2}{3-1} = \frac{1}{2} = 0.5\), just like in the original scenario!

The nature of this survey does not allow for \(\varepsilon\) values below a certain threshold. A biased coin that would produce a \(\varepsilon\) below this value cannot exist, as it would require a negative probability. The lowest a probability can be is zero, but we know that for this scenario the probability can’t be zero as that would make the odds undefined. Let’s take the limit:

That’s the infimum of how \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private this survey could be.

A generalization: quantifying the attacker’s knowledge#

From the attacker’s perspective, an \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private process \(A\) produces \(A(D)\). They are interested in knowing if one individual is in the database \(D\). Assume they know \(D\) entirely, except for the individual. Is \(D=D_\text{in}\) or \(D=D_\text{out}\)? Where \(D_\text{in}\) includes the individual, and \(D_\text{out}\) does not.

The attacker has an a priori probability of the individual being in the database, that is, \(p := P[D=D_\text{in}]\). Given the output \(O\), how does the attacker’s suspicion change? How does \(P[D=D_\text{in}\vert A(D) = O]\) compare to \(P[D=D_\text{in}]\)?

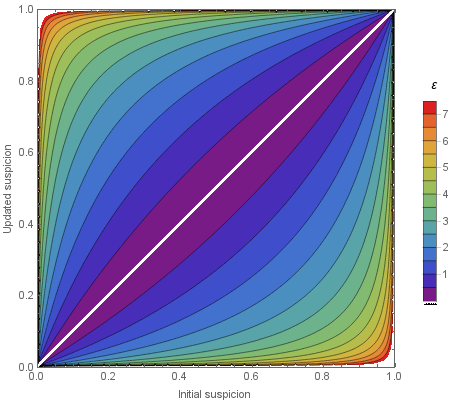

The image shows how much the probability could change for different values of \(\varepsilon\). Higher values increase how much the probability will increase. Let us derive the ranges analytically. Consider Baye’s theorem for the a posteriori probabilities for \(D_\text{in}\) and \(D_\text{out}\).

We can simplify one term and plug it in:

We now have expressions for the positive and negative events, and can calculate the odds of the a posteriori probability:

The second term of this product is bounded by our original definition for a process that is \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private:

Plugging in these bounds to the previous expression gives us:

and so:

Of course, because we only have two datasets, \(P[D=D_\text{out}] = 1 - P[D=D_\text{in}]\) and \(P[D=D_{out}\vert A(D)=O] = 1 - P[D=D_{in}\vert A(D)=O]\). Let’s plug that in:

We can now solve for the a posteriori probability and get it in terms of just the a priori probability and \(\varepsilon\):

for the right-hand side of the inequality:

similarly, for the left-hand side of the inequality:

These bounds for the a posteriori probability hold even if the attacker has less information than assumed, and so this is a worst-case scenario.

What about composition?#

The two claims from the previous article have been validated: we’ve quantified how much knowledge an attacker can obtain without making assumptions about them. The last claim, that composing two \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private algorithms produces a \(2\varepsilon\)-differentially private algorithm, can be validated.

Given two independent \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private algorithms \(A\) and \(B\), let \(C\) be a process such that \(C(D) = (A(D), B(D))\). That is, the output of this composition is a pair of outputs: \(O = (O_A, O_B)\).

Because the two algorithms are independent, \(P[C(D_1) = O] = P[A(D_1) = O_A] \cdot P[B(D_1) = O_B]\).

From the definition of differential privacy, \(P[A(D_1) = O_A] = e^{\varepsilon} \cdot P[A(D_2) = O_A]\).

Plug the definition into the equation:

As such, process \(C\) is \(2\varepsilon\)-differentially private.

2. How to achieve differential privacy#

First branch.

2.1. Differential privacy in practice (easy version)#

Summary

2.2. Almost differential privacy#

Summary

2.3. The privacy loss randome variable#

Summary

2.4. The magic of Gaussian noise#

Summary

2.5. Getting more useful results with differential privacy#

Summary

2.6. Averaging risk: Rényi DP & zero-concentrated DP#

Summary

2.7. Choosing things privately with the exponential mechanism#

Summary

3. Why bother with differential privacy?#

Second branch

3.1. Local vs. central differential privacy#

Summary

3.2. Why not differential privacy?#

Summary

3.3. Demystifying the US Census Bureau’s reconstruction attack#

Summary

3.4. Don’t worry, your data’s noisy#

Summary

3.5. Is differential privacy the right fit for your problem?#

Summary

3.6. What anonymization techniques can you trust?#

Summary

3.7. Mapping privacy-enhancing technologies to your use cases#

Summary

4. Known real-world deployments of DP#

Third branch.